Music, Abstraction, and the Return to Playing

If cultural capital becomes usable rather than encrypted, something subtle begins to change: participation stops being exceptional.

Music is a good place to observe this shift.

Anthropological research suggests that music is a universal human activity [1]. Across cultures, it appears not primarily as a product, but as a practice — embedded in rituals, social cohesion, care, and shared meaning. In many societies, music-making is not reserved for specialists. People sing, play, and move together as part of daily life.

Historically, music was less about performance for others and more about participation with others.

Over time, especially in Western contexts, music followed the same trajectory as many other forms of cultural capital. Instruments became more complex, theory more formalized, and legitimacy more tightly coupled to training and correctness. This evolution brought extraordinary refinement — and at the same time it also introduced distance.

Creation increasingly became something done by experts, while many others remained close to music only as listeners.

That doesn’t mean music became passive. Even today, concerts, dance floors, and collective listening spaces are deeply participatory in their own ways. But compared to more direct, communal forms — singing together, improvising, playing informally — participation often remains mediated, structured, or asymmetrical.

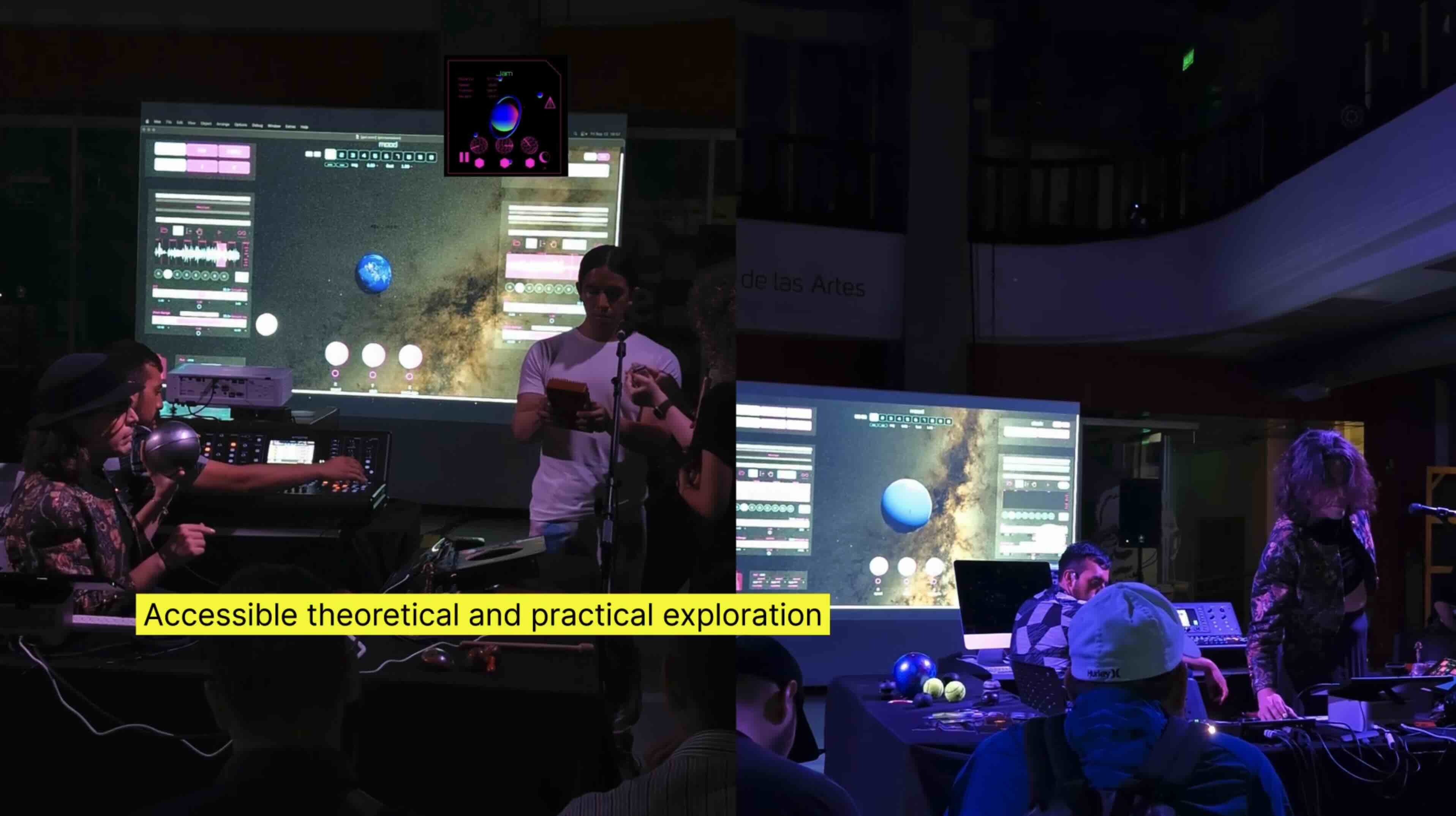

As with other tools and technologies, musical interfaces are becoming more intuitive. Abstraction is still present, but it no longer needs to be confronted all at once. You can begin through play, exploration, and listening — and let structure emerge later.

From my perspective, this isn’t about making music “easier.” It’s about restoring permission.

Listening plays a crucial role here. Research in cognition and neuroscience suggests that attentive listening develops forms of intelligence that are embodied, relational, and non-verbal [2]. It trains sensitivity, presence, and the ability to sense patterns and relationships — rather than optimize or control them.

In that sense, music is not just an art form. It’s a way of practicing how we relate — to ourselves, to others, and to complexity.

This return to accessible music-making isn’t about output, metrics, or performance. It’s about restoring music as a practice — something we do to think, feel, and connect.

We’re not moving backward.

A new loop in the spiral.

Music may be returning to where it began, with new dimensions — because we’ve learned how to place complexity behind play. In doing so, we may be rediscovering something essential: participation as a form of collective intelligence, and music as one of its oldest mediums.

References

[1] Savage et al., The Natural History of Song

[2] Stanford University, Music moves brain to pay attention

[3] Alan P. Merriam, The Anthropology of Music